Everything You Need to Know About Distress Signals

Understanding what distress signals are, as well as when and how to use them is integral for boating. Rule 37 in the Rules of the Road states:

“When a vessel is in distress and requires assistance she shall use or exhibit the signals described in Annex IV to these regulations.”

These signals can be confusing, especially for new boaters. The fact is there are many different types and many different ways they can be used. Keeping it all organized can feel a little overwhelming.

To start with, there are two major types of signals – visual signals and sound signals. What information you need to relay can affect what signal you use. Also, signals can change whether you’re in inland waters or in international waters.

Visual Signals

Visual signals can be achieved in a variety of ways. These include the use of signal flares as well as flags and other devices. There are rules for where and when visual signals need to be used and the types of signals used. When you are on coastal waters, the Great Lakes, territorial seas, and those waters connected directly to them, up to a point where a body of water is less than two miles wide, your vessel must be equipped with U.S.C.G. Approved visual distress signals. Vessels owned in the United States operating on the high seas must be equipped with U.S.C.G. Approved visual distress signals.

The following boats are not required to carry day signals but must carry night signals when operating from sunset to sunrise:

- Recreational boats less than 16 feet in length

- Boats participating in organized events such as races, regattas, or marine parades.

- Open sailboats less than 26 feet in length which are not equipped with propulsion machinery.

- Manually propelled boats like canoes, kayaks, rowboats and such.

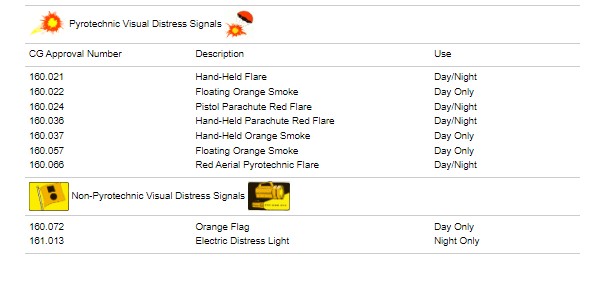

That two mile restriction means that there are bodies of water such as bays, inlets, rivers, lagoons and so on where the signals will not be required. The Coast Guard recognizes a variety of visual distress signals both pyrotechnic and non-pyrotechnic. Their website offers further details on the nature and use of these signals. As you can see, some are only approved for day use, some for night and some may be used at either time.

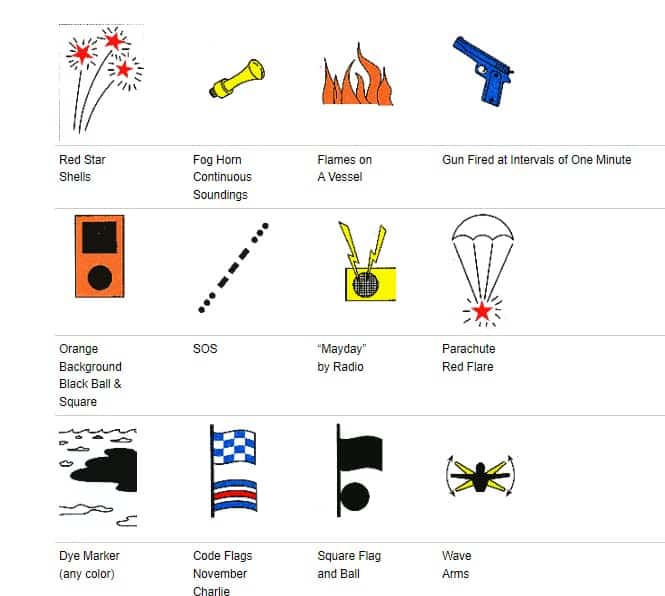

Signal Flares: This can include red stars or parachute stars. It is always a good idea to have a flare gun or similar device as part of your emergency kit on a vessel. Always make sure your flares are still usable. Flares come with a date by which they should be used so you’ll know if they’re still good. Typically this is 42 months after the date of manufacture. Red flares can be used day or night. Caution must always be used with flares. These can be with an extreme heat that can cause fires and serious injury. Always make sure you check the directions on proper usage for the type of flare you have.

One thing to keep in mind if you ever do need to use flares is to be conscious of how many you have. If you only have three flares, you don’t want to fire them all off at once. Fire one to try to get attention from another vessel. if you get a visual response in return or see a vessel approaching, then it’s a good idea to fire another flare to help them locate you. The Coast Guard will make use of a flashing blue light in search situations. If you see this, fire off a flare to signal your position to them.

Dye Markers: Dye markers are packets that can be thrown into the water when you think another vessel or a plane may be approaching. The marker produces a very bright, noticeable color that will remain on the surface of the water for some time.

Smoke Signals: This kind of signal device can either be handheld or floating. When activated, it produces a cloud of orange smoke, indicating distress. This is visible during the day for some distance. Hold it as high as you can for the best visibility. Orange smoke signals can also be used on the water rather than handheld. Smoke signals are not intended for night use as they wouldn’t be visible in low light conditions.

SOS Lights: An SOS can be transmitted with lights by performing three short flashes of light, three longer flashes, then three short flashes again. This could even be done with a flashlight in a pinch but will obviously work best at night.

Flames: You never want to have loose flames on a boat if you can avoid it. However, controlled burning can be used as a signal of distress. Burning in an oil barrel or even a metal garbage can could work in a pinch. Since fire is never meant to be on a boat, this provides a clear sign of trouble to any passing vessels. That said, you must take the utmost caution to do this carefully and safely. You would not want to lose control of fire on the deck and cause your situation to get worse.

Signal Flags: There are several types of flags that can be used to communicate distress at sea. The International Signal for Distress uses two flags. It’s Code Flag ‘N’ (November) flown above Code Flag ‘C’ (Charlie). You can also fly the orange signal flag with a black square and black circle. Obviously, flags are only useful as day signals because other vessels would not be able to see them at night. The Coast Guard recognizes the waving of an orange flag as a signal of distress.

You may have heard that flying the upside down or inverted ensign is an acceptable signal for distress. That means flying the US flag upside down. Traditionally this was flown as a sign of serious distress. However, it’s worth noting this is not an officially recognized signal. Part of the reason for that is that it can’t always be duplicated with every flag. Consider the Japanese flag, for instance. It’s a red circle in a field of white. How would you fly that upside down?

If you have no other options available, flying the flag upside down could certainly work. That said, we wouldn’t recommend it as a first choice.

Waving Arms: Even when nothing else is at your disposal, if you can get up and move you can still signal other vessels. When you are in visual range stretch your arms out and slowly raise and lower them at your sides. Make sure the movements are clear and easy to see. Sustain the arm waving for as long as it is prudent to do so.

Sound Signals

The navigation rules require sound signals to be made under certain circumstances. Meeting, crossing and overtaking situations described in the Navigation Rules section are examples of when sound signals are required. Recreational vessels are also required to sound signals during periods of reduced visibility.

When boating on any inland waters in the United States, there are legal rules regarding sound producing devices that must be followed. If your boat is 39.4 feet or12 meters or more in length, you are required to have a whistle or horn, and a bell on board. So that’s at least two distinct sound producing devices you need to have.

When it comes to international rules, you are not required to have a bell on board. That said, it’s always better to be safe than sorry and we recommend you have both the bell and a whistle/horn just in case.

If your boat is under 12 meters or 39.4 feet, the rules are slightly different. You don’t require a bell but you do need to have some means of making an “efficient sound signal to signal your intentions and to signal your position in periods of reduced visibility.”

What qualifies as an efficient sound signal? Again, a whistle or horn is best, but a bell may suffice as well. In an emergency you can even bang pots and pans together if you have no other option, but that’s something you should only do when all else fails.

In terms of reduced visibility, we’re referring to low light conditions including rain and snow. Any of these could require the use of a sound signal to alert other boats to your presence and prevent an accident.

Not all sound signals need to be used during low visibility situations, but that is one situation where they must be used. As you can imagine, visual signals are not going to work as well during heavy snow or fog, for instance.

When to Use Sound Signals

Having the ability to use sound signals is important. But how do you know when to use them? And exactly what do you need to do to use them properly?

Sound signals need to be used when you are in visual range of another vessel. When you are in a position to meet or cross paths at a distance within ½ mile you need to use a sound signal. We can call these Passing Signals. Keep in mind, these signals are not to be used in foggy or other low visibility conditions. Low visibility and warning sound signals are different. We’ll cover them after the passing signals.

Passing Sound Signals

When you are approaching another boat and wish to pass these are the signals you should use. A short horn blast is considered one second in length. This can also be accomplished with a whistle as well.

1 Short Horn Blast: This will signal your intent to pass a vessel on your Port Side.

2 Short Horn Blasts: This will signal your intent to pass the vessel on your Starboard Side.

If you’re afraid you might forget which is which, there is an easy way to remember.

Port = one syllable = one horn blast

Starboard = two syllables = two horn blasts.

Warning Sound Signals

These are signals to alert other boats that there is something they need to be aware of. These make use of a mix of short blasts, which we’ve already seen, and prolonged blasts.

Unlike a short blast of one second, a prolonged blast should last four to six seconds. It needs to be clear to any other vessels that a prolonged blast is longer than a short blast. That way no dangerous mistakes will be made.

Short horn blast = one second in length

Prolonged horn blast = four to six seconds in length

Here are some typical warning signals you may hear on the water. These are the ones you will be most likely required to perform as well when you are around other boats

3 short horn blasts: Use this signal to alert other vessels that your engine is in reverse and you are backing up.

5 short horn blasts: Use this signal to indicate an unspecified danger. Also, use this to indicate to another vessel that you do not understand the approaching boat’s intentions and they need to clarify.

One prolonged blast: This signal is a warning. Use it to let other vessels know when you are exiting a dock or berth. It can also be used as a warning when you are approaching an obstruction, or a blind turn.

1 Prolonged Blast Repeated Every 2 Minutes: Use this signal when you are in a vessel under power but your visibility is restricted. If you were traveling through fog you would need to do this.

1 Prolonged Blast Plus 2 Short Blasts Repeated Every 2 Minutes: This indicates you are in a sailing vessel in limited visibility. The repetition every two minutes is very important as new vessels could be entering the area but unable to see you and will need to be alerted.

Low Visibility Sound Signals

Unlike conditions such as reversing or taking a blind turn, low visibility is a sustained situation. Fog could roll in and stay for hours. That means these low visibility signals need to be done repeatedly. You never know when another vessel may be approaching. That means you need to be sure you’re providing adequate signals for as long as visibility is limited.

If conditions are such that you cannot see other boats then the following sound signals are necessary.

2 Prolonged Blasts Repeated Every 2 Minutes: This is the signal that is used when you are in a power boat that has stopped. You are not anchored but you are not making way.

Five Seconds of Rapid Bell Ringing: This is the signal to use when your boat is at anchor. Ring the bells rapidly for 5 seconds at intervals of 1 minute.

3 Bell Strokes + 5 Seconds of Rapid ringing + 3 Bell Strokes: This is more of an emergency type signal to use. When your boat is aground, ring the bell three times then rapidly ring for 5 seconds, and ring three times again. This must be repeated every minute

Additional Signals

There are other distress signals that can be used in certain circumstances when the ones we have covered are not options. If something happened to your visual or sound making devices, you could try these to indicate you require assistance. These include;

A Gun: When fired at one minute intervals, a gun can be used to indicate distress. This should not be your first choice if it can be avoided. That said, if it is what you need to do make sure you exercise the utmost caution.

High-Intensity Flashing Lights: This can be used on inland waters. If you have no other means of signaling, use something like a bright lantern or flashlight. Flash it at regular intervals, 50 to 70 times per minute. This can be done very simply in a pinch by turning the light on and off, or waving your hand in front of it to produce those intervals.

Fog Horn: A continuous and sustained blast of a fog horn can be used to indicate distress.

Radio Signals: There are several ways you can indicate distress by radiotelephone or similar device. The old school Morse Code signal for SOS is still an acceptable method of communicating that you need assistance. This is accomplished by three dots, three dashes and three dots. In audio terms this is three quick, one second blips, three longer two to three second blips, followed by three quick one second blips again.

EPIRB: An EPIRB is an Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon. We recommend all boaters keep one of these on board. Because they are emergency devices they are rugged and withstand some serious abuse. Even if your boat were to capsize a good EPIRB will remain afloat and transmit an emergency signal. Satellites monitor signals from EPIRBs allowing them to be tracked so your location can be quickly identified in an emergency.

Your VHF Radio

The best tool you have for communicating distress at sea is your VHF radio. The visual and sound signals we have listed here are all valuable tools and can save lives. But the VHF radio should definitely be your first choice if and when you need to communicate any issues with your vessel. Make sure yours is working order before you head out on the water. Also make sure everyone on board is familiar with its use.

It seems like common sense to have a radio on board but not every boater does. Each year the Coast Guard is sent out to rescue dozens of vessels that did not return at their expected time. Something went wrong and the boat was in distress but the information was not relayed directly to the Coast Guard because the boats were not equipped with a functional VHF radio. It really can save lives.

Mayday calls are the most well known emergency call that can be made on a VHF radio. Make sure you’re never making a false Mayday call as that can lead to very steep fines of up to $250,000. You could also face up to 6 years in prison. So you definitely don’t want to do this unless you’re sure your situation is a true emergency.

Making a MayDay Call

Mayday calls to the Coast Guard are to be made in dire, life-threatening situations. Only make a Mayday call if one of these situations applies.

- Your vessel is taking on water

A serious collision with another vessel

A fire on board

Capsized boat

A medical emergency

If you are certain that it’s appropriate to make a Mayday call, follow this process.

- Turn your VHF radio to Channel 16. That’s 156.8 MHz. This is the international distress frequency.

- Hold down the transmitter button on your radio. Now repeat MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY. Say “This is vessel______”

- Repeat this message clearly 3 times in a row.

- Identify your boat for the Coast Guard or any others who may respond to your call. Give a description of the vessel. Provide your location with GPS coordinates if possible. Tell them how many people are on board and then explain your emergency.

- When you are finished, say “over” to indicate the message is done. You can now take your finger off the transmitter button and wait for a response.

- Give responders about 30 to 60 seconds to reply to you. This can seem like a long time in a serious emergency but try not to panic. If you do not hear anything after a minute, repeat your message.

Emergency Use Only

We touched on the fact a Mayday call must be a true emergency. Fines and prison time await those who misuse the Mayday system. That said, the Coast Guard prohibits the display of distress signals except when a distress actually exists. You should only use distress signals when help is close enough to see the signal. Make sure you have a visual ID of another vessel before using a visual or sound signal because it may be wasted as a result. The U. S. Coast Guard recognizes both pyrotechnic and non-pyrotechnic devices.

Non-Emergency Assistance

So we saw the situations in which it’s okay to use a Mayday, but what do you do in less pressing circumstances? You may still need aid but no one’s life is in danger. This could be something like your engine failing, running out of fuel, or a similar issue in which assistance is needed but no one will die if it doesn’t arrive right away.

In these non-emergency situations, a Pan-Pan call is the kind of call you want to make. The format is similar to a Mayday call but the urgency is obviously less. You can always upgrade to a Mayday later if things get worse for you. But if it’s not life threatening, here’s how to make the call.

- Turn your VHF radio to Channel 16. This is the international distress frequency.

- Hold down the transmitter button on your radio. Now repeat PAN-PAN PAN-PAN PAN-PAN. Say “This is vessel______”

- Repeat the name three times but you only need to do call letters once.

- Identify your boat for the Coast Guard or any others who may respond to your call. Give a description of the vessel. Provide your location with GPS coordinates if possible. Tell them how many people are on board and then explain your situation and what you need.

- As with any other call for help, give responders about 30 to 60 seconds to reply to you. If you do not hear anything after a minute, repeat your message.

The Bottom Line

Having appropriate visual and sound producing signals on your boat is essential for safety at sea. Not only are they a good idea, they’re required by regulations. Make sure you are familiar with how to use whatever aids you have before setting out. Make sure others on the vessel are also skilled in their use, just in case.

We recommend no boat ever go on the water without a functional VHF radio, working visual and sound signals, and an EPIRB. When it comes to your safety, you can truly never be too careful. As always, stay safe and have fun.

Categories: nauticalknowhow